Two Kinds of Depression

Sensorimotor and despair

The more I introspect about my own depression and the more I talk to others about theirs, the more I begin to suspect that this we’re using a single word, ‘depression’, to refer to two distinct experiences.

Or at the very least, we’re conflating two distinct problems in the brain because they often share symptoms and causes.

Depression As Despair

This is the internal experience people tend to associate with depression. It’s a hell of anhedonia, a gaping pitiless chasm from which no hope and no joy can emerge.

It’s thinking your life is meaningless and that maybe death would be better. It’s a dull blank slate of an inner world, as if the colorful tapestry that your thoughts once wove died and was dyed in a monotonous beige. Where once there was color and light and life and variety as the spice thereof, now everything tastes the same, looks the same, feels the same.

The natural human response to this apocalypse of emptiness is hollow despair.

This is the person that you’d never notice was depressed, never realize was dead on the inside. They go about their life, shambling from home to work or school and back, a zombie without hunger because feeling hunger would be an improvement.

This is key: the despair is internal. It’s a surprise when you discover this person is depressed.

They can still do their job.

They can still hang out with friends.

They can still get out of bed and shower and brush their teeth and do the dishes and all the other little chores that life is made of.

They’re just suffering the whole time, unable to feel satisfaction or happiness at any of it.

I think that people with despair-based depression often conceal their mental state, mostly because they can. The problem they have is invisible; hiding it is easy.

Of course, this burden takes its toll over time.

The longer someone lives with this kind of depression, the harder things get. They may start to act differently - slow down, have less energy, laugh less, smile less, stop going out, etc.

But the causality is clear: the despair and anhedonia cause the slowdown, the retreat into self and withdrawal from life that characterizes depression. This isn’t necessarily the case for the second type of depression.

Depression As Sensorimotor Damping

In physics, there’s something called a damped oscillator. Imagine a spring with a weight on it, or a half-deflated basketball. These oscillators oscillate - they do go back and forth - but they’re severely impeded. They don’t spring or bounce or swing as much as they would normally.

It takes far more energy to get them to move than if they weren’t damped.

In a human brain, this is what I call sensorimotor depression. It’s a general damping of the whole system, such that thought, action, and sensation are all suppressed.

This kind of depression is the kind where you never get out of bed, because it takes too much energy to spur yourself to movement. It’s the kind where your gestures and speech are noticeably slower than they would otherwise be. It’s the kind where you can’t solve problems because it feels like your brain is full of fog, and you have to practically swim through molasses just to remember what it is you’re supposed to be doing.

The only way to hide this kind of depression is to cancel plans, not go out, and otherwise not interact with people, because anyone who knows you is going to find it very obvious that you can’t function the way you normally do.

This kind of depression can easily ruin your life or otherwise send it veering wildly off course. After all, if you can barely get out of bed to eat and relieve yourself, how do you think you’re going to hold down a job? Finish a degree? Spend time with friends? When you don’t have the energy to do anything, you wind up doing nothing - and so your life becomes a sea of nothingness, a dull plod from day to day where you exist just to keep existing.

Sensorimotor depression can include despair, but it doesn’t have to. Feeling things takes energy, so it’s also taxed like everything else, but the despair isn’t the cause of the damping, it’s a symptom. When you can’t do anything and your life falls apart because of it, when there’s no cause or end or cure in sight, despair is a natural response.

Distinctions

These two types of depression are comorbid:

When you despair, doing anything becomes pointless, so you stop doing things.

When you can’t do anything, you despair.

They feed into each other and intertwine, the same way that anxiety and depression often go together. But there are differences, the questionnaires I’ve had to do when visiting doctors make that clear.

My experience has mostly been sensorimotor depression, which means that on some measures of depression, I’ve scored very highly: moving slowly, low energy, lack of motivation. But I have little symptoms of suicidal ideation or feeling intense shame or hatred towards myself.

Dimensions of Depression

When these measures are collapsed into a single number, it can make my depression look middling, when the reality is that it’s very high in one dimension and quite low in another.

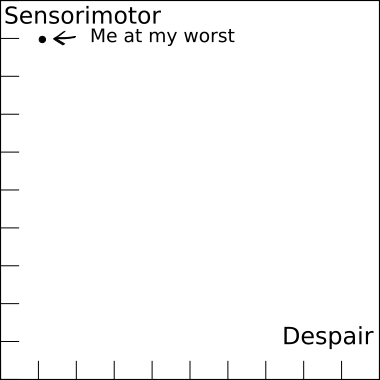

In more precise mathematical language, if depression is measured on a plane with an x-axis and a y-axis, where the x-axis represents despair and the y-axis represents sensorimotor damping, and the scale is from 0 to 100, I’d be somewhere around (10, 90) at my worst.

The problem is that standard psychological questionnaires measure the magnitude of one’s depression as:

which is an average of two numbers, in an attempt to reduce the dimensionality of the problem. It would be like a doctor averaging a broken arm and a stubbed toe and reasoning that their patient is only moderately injured.

I think that this is a small example of an important phenomenon in psychology. A mind is an incredibly high-dimensional thing: any two minds can be different in an almost infinite number of ways, and yet to do any kind of psychology, psychologists have to collapse that infinity into a few discreet numbers.

IQ, for example, is meant to represent a measure of intelligence, a high-dimensional quantity collapsed into a single number. Standard tests of personality face the same problem: a personality can vary along a quasi-infinite number of dimensions, so reducing it to four (Myers-Briggs) or five (Big Five) hides a great deal of information.