One To Many Relationships

Different institutions can have vastly different scales. By my definition, an institution can range from two people running a soup kitchen in a basement all the way up to entire departments of the US Federal bureaucracy.

The former may be trying to help out a few hungry people in the neighborhood; the latter may be attempting to administrate billions of dollars and thousands of employees in order to address a social ill felt by millions.

What is true of any institution at any scale, however, is that it features a one-to-many relationship with the people (or problems) it addresses.

A single soup kitchen feeds multiple people; a single homeless shelter houses many.

A single government department administrates for an entire country.

Here I argue that this one-to-many relationship incentivizes institutions to create one-size-fits-all solutions, and some of the implications of this.

Why One Size Fits All?

The one-to-many relationship that an institution necessarily forms with its constituents comes with an incentive to deal in one-size-fits-all solutions.

After all, it isn’t possible for a single organization to customize its solution and approach for each individual it seeks to help. Customization is generally a luxury bought at high price, and when the budget is finite and spread thin, it isn’t one that can be afforded.

There are, however, more specific reasons why institutions tend towards one-size-fits all solutions, some of which are addressed below.

Fairness

Imagine a soup kitchen where certain people get twice as much soup as others, or a regulatory agency where a specific company is treated favorably compared to all others in its industry.

In both cases, we might accuse the institution of being unfair. Inequitable. Showing favoritism.

In order to avoid such accusations (or because those running the institution feel strongly themselves), a one-size-fits all solution may be applied.

Everyone gets treated equally. Everyone gets the same amount of soup. Every company gets the same regulatory scrutiny. And so on.

Complexity

Complexity is expensive, difficult, and error-prone. The more complicated the institution’s solutions become, the more overhead they require. More administration, more bookkeeping, more auditing, more procedures, more ways to screw up.

Think about a hospital: each patient comes in with a unique combination of genetics, history, environmental factors, and symptoms. While it’s possible the same treatment may work on two different patients, it’s never guaranteed. Every medical intervention needs to be customized to the patient’s gender, weight, blood type, etc.

It’s ridiculously complicated, expensive, and the bureaucracy supporting it has grown enormous.

If an institution wants to be effective, the simplicity of a one-size-fits-all solution is extremely tempting.

Want to fix homelessness? Give everyone a home.

Want to fix healthcare? Medicare for all.

Simplifying solutions leaves more time, energy, and funding to spread those solutions to more people.

Last Mile Problem

I learned of the Last Mile Problem from the field of telecommunications.

Specifically, if a company wants to provide telephone service to every house in a suburb, they first run the necessary wires (back when telephones required wires) hundreds of miles from the central hub to a junction within or near the neighborhood.

This junction, less than a mile from every house, now has to be connected to each individual house - which requires the same amount (or more) of work as the hundreds of miles of wire connecting the hub to the junction!

In other words, mostly solving a problem is easy. Fully solving it is hard.

This is also stated as the 80/20 rule: 80% of the solution (going from hub to junction) takes 20% of the work, and the remaining 20% of the solution (going from junction to each house) requires 80% of the work.

It’s much simpler, easier, and cheaper to disregard the 20% of the solution that’s difficult and finicky in favor of the 80% that isn’t. And if the solution doesn’t work perfectly for everyone, well, nothing’s perfect, right?

Problem Distributions

Real-world problems can exist in one of two possible places: Mediocristan or Extremistan. The terms were coined by Nassim Taleb as a way of thinking about distributions of values.

One-size-fits-all solutions work reasonably well in Mediocristan, but fail in Extremistan.

Mediocristan

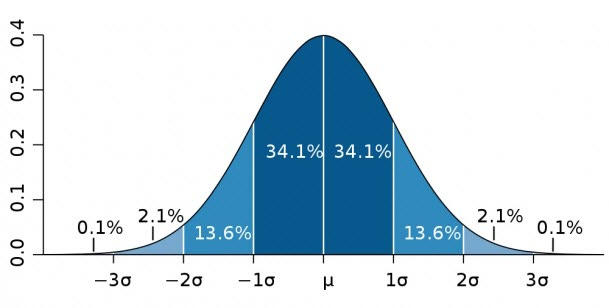

Mediocristan is the home of the normal (Gaussian) distribution, the famous bell curve where the number of samples vastly different than the mean is very small.

Mediocristan is the home of distributions of height, weight, and IQ. While there are always a few outliers, nobody is ten times as tall as another person, or fifty times heavier, or a million times smarter.

One-size-fits-all solutions are made for Mediocristan. “One-size-fits-all” originally refers to a piece of clothing, which (given that clothes are sized based on human height and weight) can work. A piece of clothing with certain dimensions will fit a large percentage of the population.

On the other hand, a one-size-fits-all jacket wouldn’t fit on the Statue of Liberty - then again, she lives in Extremistan.

Extremistan

Real life, as Nassim Taleb points out, often takes place in Extremistan, where things follow power or log distributions. And one-size-fits-all solutions are not possible in Extremistan.

Take education - IQ may be distributed normally, but the difference in educational needs between the brightest students and the most disabled is vast and certainly not linear. There is no solution that will work for both.

There isn't even a single solution that will work for every single learning disability; dyslexia requires a very different kind of learning environment than Down Syndrome, and so on. And then there's all the students in between, each interested in different things, each with their own values, goals, dreams, experiences...

Everyone coming to a soup kitchen needs roughly the same thing: calories and nutrients. But for homelessness itself, the causes can vary wildly: various mental or physical disabilities, trouble with the law, abusive situations, and so on.

A one-size-fits-all solution cannot possibly work for any problem in Extremistan - and unfortunately, that’s where a lot of real-world problems live.

Implications

Institutions are incentivized to execute one-size-fits-all solutions to the problems they seek to address.

What does this imply about how we should design our institutions?

One thought is that the problem an institution addresses should be kept small enough in scope that a one-size-fits-all solution has a chance of working.

Feeding a small number of homeless people, or administering a single neighborhood, or educating a single classroom of similar students - these are solvable problems for a one-size-fits-all solution.

Another thought is that a small menu of pre-created one-size-fits-all solutions may work better than a single such solution. Take the construction industry, for example: there are a small number of different construction systems for different conditions, like timber frame, masonry, and steel. Each such solution has benefits and drawbacks, and the availability of multiple known solutions allows people to pick the one that works best in their particular circumstance.

The biggest implication, however, is that the institutions we have today are incentivized to use solutions that can’t possibly solve real-world problems.

Real-World Problems

A cursory search for the most important issues in the world today brings up many familiar causes:

Poverty

Climate Change

Existential Risks (Nuclear War, Pandemics, AI, etc.)

Healthcare

Freedoms/Rights

Each of these issues is complicated, and the institutions that are supposed to address them have taken on an incredibly heavy burden.

It’s important to understand, however, that there are no magic bullets to solve any of these problems. No single solution, no matter how one-size-fits-all, could possibly fix climate change or healthcare.

No single treaty removes the risk of existential threats.

No individual government program erases poverty.

These issues are fractally complicated - each can be broken down into many sub-issues, all of which are still complicated, and each of those sub-issues can be broken down, and so on.

Imagining that there is a single, one-size-fits-all solution to any of them is a fantasy.