Scarcity and Post-Scarcity

Post-Scarcity societies are free, not just of want, but of the fear of want

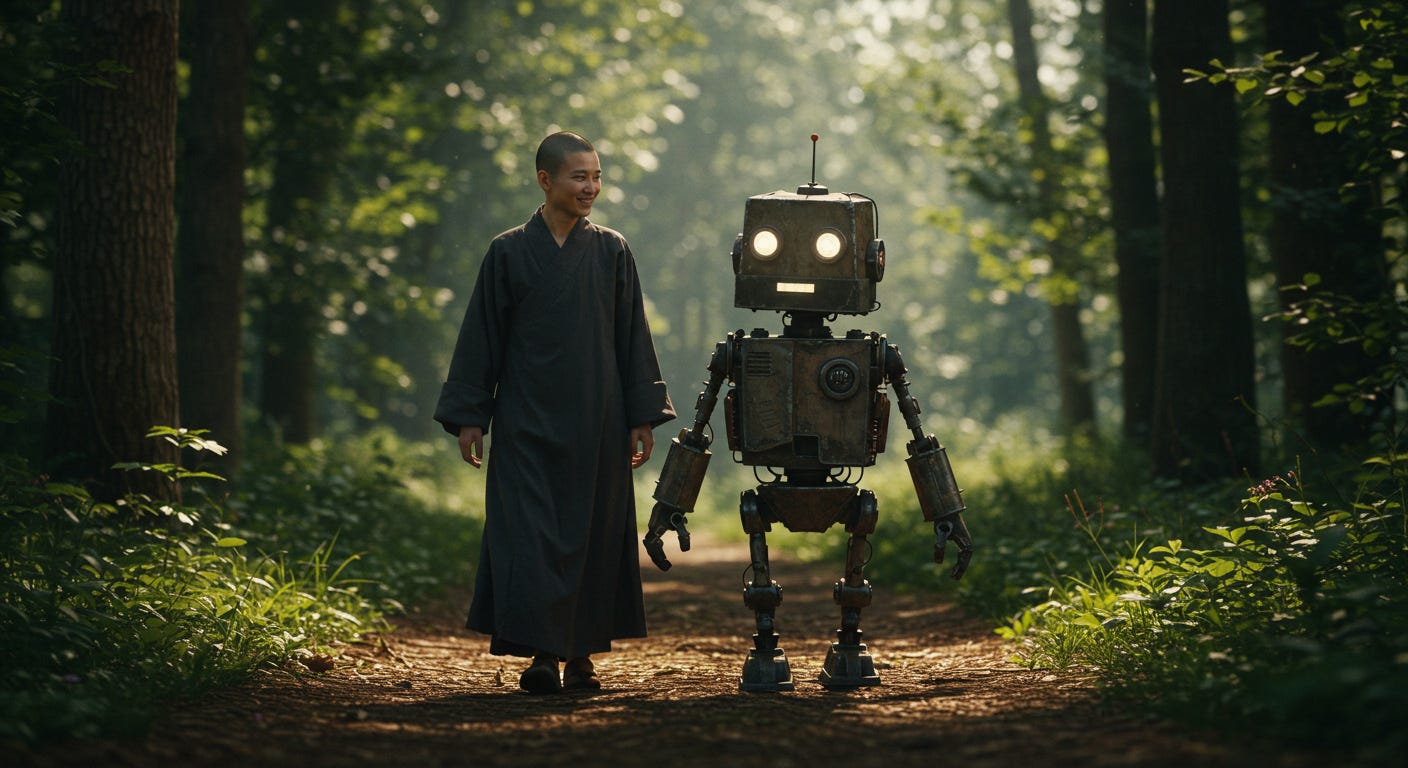

I recently read the Monk and Robot series by Becky Chambers, which currently consists of two books: A Psalm for the Wild-Built and A Prayer for the Crown-Shy.

The series takes place in a post-industrial society called Panga, a vision of humanity after its ‘factory age’, where everyone lives in harmony with nature, using copious solar energy and biodegradable materials for everything.

Something bugged me about this society - it was almost too peaceful, too serene. It was a perfect vision of a solarpunk civilization, a Utopian dream of a humanity that had finally grown beyond the need to control and consume everything there was. It wasn’t until the second book, however, that I finally realized what that nagging sense was.

Suspension of Disbelief

Every fictional story requires a certain suspension of disbelief, as does the occasional nonfiction story.

In my preferred genres of fantasy and science fiction, suspension of disbelief is rather natural - when I read Harry Potter, I’m not thinking about how magic isn’t real; when I read Dune, I’m not thinking about the logistics of interstellar travel. I’m simply swept away to the world the author has built.

That being said, some disbeliefs are easier to suspend than others.

I’ll suspend my disbelief in magic, because I know I’m reading a book about it, but I still expect the magic of a book to make a certain amount of sense. There should be some kind of system, some form of rules or limitations. If magic can do literally anything at any time without any cost, then why don’t the protagonists just wave their wands and fix all their problems?

When I read the Monk and Robot series, I found I was having a hard time suspending my disbelief, not about sentient robots or solar technology, but rather about the nature of the society they lived in and the humans that inhabited it.

To put it bluntly, the humans in the Monk and Robot series are unlike humans on Earth in some very key ways, and it wasn’t until the topic of a currency came up in the second book that I could nail down exactly how.

Not-Currency

The society in the series uses the concept of ‘pebs’, not as a currency, but as a way to keep track of what one has done for the community. There’s a whole conversation about it where Sibling Dex explains how it works to Mosscap (the robot); a point is made in the story about how this aspect of Pangan society functions.

Everyone has a pocket computer, and they’ll transact in pebs on the computer the way that we transact in currency, with one key exception: the number of pebs you have is ultimately meaningless. You can spend pebs to buy goods or services, you can earn pebs by selling goods or services to others, just like with money, but unlike with money you don’t need to make pebs to spend them.

Pebs, Sibling Dex explains, aren’t a currency: they’re a way of accounting for when someone has done something for the community. And this is exemplified in how debt works in this society, which is to say that it doesn’t exist.

There is no concept of loaning or borrowing pebs; rather, a person can simply have negative pebs, and that’s fine. They can still go out and spend pebs, as many as they want.

When Mosscap asks Sibling Dex about what happens if someone has a large negative total of pebs, Sibling Dex replies that it happens sometimes, and clearly just means that the person with the large negative total needs help, so their community helps them - a lovely vision of a possible future.

This kind of not-currency only makes sense in a society that is fundamentally post-scarcity and is utterly unrealistic for the human beings that inhabit the world today.

Our Society is Scarcity-Based

Most people in most first-world countries currently have enough material resources: food, water, oxygen, shelter, etc., to meet their material needs. Even homeless people in America, however unpleasant the experience is, can generally get by day to day.

We produce enough calories in food to feed everyone, and our civilization is capable of purifying enough water for everyone to drink their fill and building enough housing for everyone to have a roof over our heads.

Our problems are distributional, not rooted in an inability to produce sufficient material goods.

So why aren’t we living in a post-scarcity society?

Well, the obvious answer is that there are plenty of physical limits on what we can produce, limits that we wouldn’t expect a post-scarcity society to have, but there’s a more insidious answer that’s harder to deal with. Technological progress has increased over the past few hundred years and will likely not slow down, meaning that the physical limits on our productive abilities get loosened every year. Global population is projected to peak and decline soon, so at some point in the future there’ll be plenty of stuff per person.

Even then, due to resources not being infinite, people still need to make a living. Just because there’s plenty of stuff doesn’t mean there’s plenty of everything. Services like healthcare and education are incredibly expensive, and so the fear of not having enough money for college, healthcare, retirement, etc. is still a very real force in our world.

But the more insidious issue is this: scarcity leaves scars. On the human psyche, on our culture, on our history. And those wounds cause us to act in certain ways that preclude us from living in a post-scarcity world - from being like the people of Panga.

Internalizing Scarcity

A common example of this is the way that objects are passed down in families. It used to be the case that objects were scarce: fine china, a wooden boudoir, jewelry - these were expensive, difficult to make, and worth passing down to one’s children. Nowadays, however, these things are much cheaper relative to modern incomes, and so there is far less need to pass them down the generations the same way.

Yet the elderly still try to pass these heirlooms down, to varying success. Growing up in a time of scarcity makes people internalize a fear of not having enough, and they don’t lose that fear just because the age becomes one of abundance.

How many generations do you think it would take of post-scarcity living, before people can live never knowing the fear of not having enough? How long would it take culture - stories, history, the trauma of generations reaching forward through time - to heal past the ever-present anxiety of deprivation?

People don’t hoard things nowadays because they need them; they hoard because they can’t escape the fear, the anxiety, the quiet sense of impending calamity that comes from some sort of trauma in their life. More stuff isn’t a magical solution to that fear, and a post-scarcity economy isn’t going to magically fix the people in it.

We still live in a scarcity-based society, not because we can't make enough stuff to meet our needs, but because we're still motivated and driven by a fear of not having enough.

The cultural memory of scarcity is real and sufficient to keep us from becoming post-scarcity. To be beyond material scarcity, you can't just have enough, you have to no longer fear not having enough. And that fear has existed for thousands of years and shaped human biology, culture, and evolution. Our bodies crave calorie-dense foods and pack on weight because they’re adapted to environments where calories are scarce.

The stories we tell each other involve great wealth because great wealth has always meant freedom from deprivation - how many Disney characters either begin as or end up royalty? And the part of royalty that we see isn’t the business of ruling, of administrating taxes or defending territory, but the wealth and safety that come with it. Cinderella no longer has to cook or clean; Bell is safe from the villagers and has enough books to last a lifetime, etc.

Scarcity pervades us, from our culture to our very genes. We are not going to be rid of something so ingrained so quickly.

Panga is a Post-Scarcity Society

In Panga, people have what they need and seem to have learned to not want a whole lot more than that. Sibling Dex’s family are farmers, and they seem genuinely happy with their lives, as do the other characters we meet along the way.

What’s striking isn’t that they have enough, even though they do, it’s that they genuinely don’t seem to have a desire for more. No one we meet wants to be rich or famous, or even just more rich or famous than anyone else.

When Sibling Dex returns from the wilderness with Mosscap alongside them, they gain some manner of celebrity from being the first person to meet a robot in ages (and the one travelling alongside the robot). This celebrity makes them somewhat uncomfortable (a pretty natural response), but while we see others mention Dex’s newfound notoriety, we see zero jealousy, envy, or other negative reactions.

Since Sibling Dex is the narrator it’s possible these feelings were present and they just didn’t see them, but that isn’t the impression I got from the books. The people of Panga genuinely don’t seem to compete over resources or money or fame. It’s refreshing but bizarre to witness, like watching human-shaped ants all cooperating with one another.

These people are living without a fear of deprivation. Their stories, their gods and religion, aren’t marked by a scarcity of resources. Their culture is all about fitting in and adapting to the cycle of nature and doesn’t seem to involve things like competitions to acquire more wealth or a desire for power or fame.

I think a large part of why the world of the book seems so idyllic is that people aren't afraid of not having enough.

Unanswered Questions

There are a few unanswered questions I have about Panga. This isn’t any kind of reflection on Becky Chambers - the world is beautifully realized - but the books are short and finite and not interested in answering every possible question about how the society works.

There’s no real description of forward progress or exploration. Pangans consciously don’t expand into the wilderness, and we get no notion of any kind of sustained population growth or space exploration. There’s little indication of technological progress that hasn’t already happened in their transition out of the ‘factory age’.

There’s no explanation of why someone would choose to do an unpleasant job in this universe. Why deal with garbage when you could instead be an artist, and in Pangan society money is no concern so you can support yourself either way? Who would want to be a plumber in this society, or do dangerous work? In real life the demand for these jobs is met because the salary associated with them rises until the job market is saturated, but Panga doesn’t really have salaries or real money, so…?

Humans Would Have to Change Substantially to Make a Post-Scarcity Society Possible

So much of human behavior can be explained by our desire to win zero-sum games - to grab more of a fixed pie. Whether we’re fighting over real resources (like oil or food or strategic minerals) or more abstract but still finite things (money, status, fame), we hoard and we grab and we fight and we compete, and we’re rarely satisfied with what we have. This behavior of ours is rooted in a fear of not having enough, combined with a hedonic treadmill that causes us to grow bored with what we already have.

These aren’t shallow facets of humanity. They’re deeply ingrained in us, forged from millions of years of life evolving under conditions of competition and scarcity. A few generations and a commitment to living in harmony with nature would not be sufficient to alter humanity so much that a truly post-scarcity society becomes possible.

For such a society to happen, I see three necessary metamorphoses that humans (and humanity) would have to undergo:

People would have to be unafraid and unscarred by scarcity.

This we’ve already seen is difficult enough, given our history, biology, and culture.

There would have to be (basically) zero bad actors.

No one in Panga appears to take advantage of the kindness of others. We don’t see any psychopaths, or even a hint of their existence. People don’t defect in Panga, in the game-theoretic sense of the word. A large part of the reason Panga seems so tranquil is that there’s no police, no threat of violence, and that can only be the case if everyone is more or less rule-abiding.

There would have to be no great threat of calamity (invading armies, etc.).

Panga is not threatened by a warmongering neighboring state, as many places in the real world are. They don’t have to institute a draft to defend themselves. Additionally, while they experience bad weather like any other society, there is little evidence of calamitous earthquakes, tsunamis, or other disasters that might force people into very difficult situations.

Conclusion

I enjoyed reading the Monk and Robot series. It’s a wonderfully written little meditation on consciousness, nature, and the meaning of life. But it’s important to understand that, for all that it wears the trappings of science fiction, the setting of the world is fundamentally fantastical. Not because the technology is magical (it isn’t) or because robots becoming sentient out of nowhere is unrealistic (humans became sentient at some point, after all), but because the vision of humanity and humans in the novels are so different from the humans of reality.

They look like real-world humans, talk like them and resemble them greatly, but they lack the scars that real-world scarcity has left on the human psyche. They seem in some ways more innocent than we could possibly be.

I do believe that Panga represents a good ideal to strive towards - not my first choice, but any society where people are happy making their own way and not hurting each other is a good goalpost. I just don’t see a straightforward path from our society to theirs. The technology - sure. The people? Not so much.

Well put. I enjoyed Monk and Robot as well, and it is a nice idealistic future the author envisions. But it seems to effectively be heaven on earth: in the sense that people's sinful tendencies have been removed. The line dividing good and evil, contra Solzhenitsyn, no longer cuts through every human heart. Or what evils there are are extremely minor... I think we see a little pettiness, a little failure to empathise, but no cruelty, and as you say no greed or desire for status.

And while it's nice enough to read about, any attempt to devise such a society in the real world is going to have to be robust to bad actors, to people who are cruel and mean just because they can be. (At least until Jesus comes again to truly remove all sinfulness.)