Lougle

Or: How the idea of a thing is not its name.

Time travel movies can be complicated and difficult to understand, like Tenet and Primer.

They can be heartwarming like Groundhog Day, action packed like Edge of Tomorrow, or serious like Looper.

And then there’s Hot Tub Time Machine.

In Hot Tub Time Machine (HTTM), three friends (and a tag-along) on a ski trip travel back in time via a magical hot tub to 1986. Warned by a mystical repairman, they set out to recreate the events of the past so as not to break the space-time continuum.

Towards the end of the film, Lou - the character for whom the ski trip was taken - decides to stay behind in the past, and when the rest of the characters catch up with him, he’s a billionaire, having founded the company Lougle.

Lougle. As if there was a Google-shaped hole in the world, and whoever came up with a similar-sounding name could cash in on filling it with nothing but a few letters and a vague idea of what it did.

Lougle.

(There’s also the band Motley Lou, but whatever. The point stands.)

Google

From Wikipedia:

Google was founded on September 4, 1998, by American computer scientists Larry Page and Sergey Brin while they were PhD students at Stanford University in California.

All the way back in the Before Times - before COVID, before social media, before the internet as we know it today - navigating the World Wide Web was a lot less straightforward. Things were less interconnected, less linked, less clear. Search engines existed, but were hardly the portals to all knowledge they are today.

There was a key innovation missing.

While conventional search engines ranked results by counting how many times the search terms appeared on the page, they theorized about a better system that analyzed the relationships among websites.[29] They called this algorithm PageRank; it determined a website's relevance by the number of pages, and the importance of those pages that linked back to the original site.

When you want to find a website, you’re not just looking for something that matches the exact terms you searched for. You’re looking for something that other sites agree matches what you search for. There’s a recursive element to the internet; the importance of a website depends upon how many other websites reference it, and how many references a website gets depends on its importance.

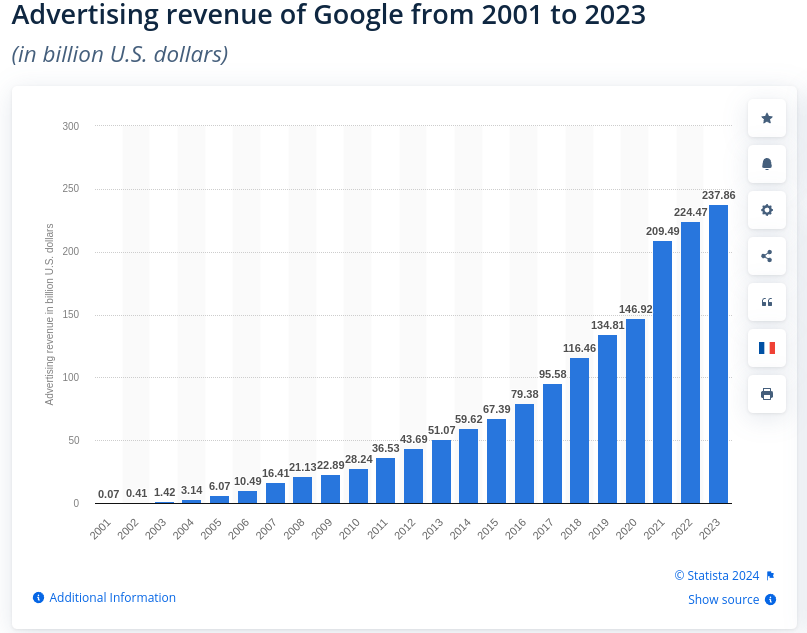

This was the spark. The fuel was ad revenue. Advertisers pay based on the reach of the platform they’re advertising on, and when Google became most people’s first-stop shop for the rest of the internet, its ad revenue became obscene.

That graph is why Google (technically Alphabet, for corporate reasons) is one of the big tech companies of today. It’s why the word google is now a verb meaning ‘to search for on the internet’. And it’s why the company’s founders are wildly rich.

History Is Not A Script

In the movie, Lou is presented as something of an idiot. He is very, very much not a Stanford PhD student, nor is he capable of building, let alone imagining, a company like Google.

This is played for laughs in the film and its sequel, but I think there’s a real point to be made here.

The movie - not Lou, the movie - presents history as a predestined sort of script, where if you know the lines ahead of time, you can waltz in and replace the lead actors with ease.

It’s as if something Google-shaped was always going to happen, and just by traveling back in time and knowing what that was, you could preempt the natural order and fill the void yourself. It wouldn’t take intelligence or business acumen or the ridiculous hours Brin and Page put in to found their company, no.

It just takes being in the right place, just a smidge before the right time, and all of the wealth and fame can be yours.

Lougle.

As funny as the movie is (and it is funny), it’s this bit that rankled me. It betrays what I suspect is a common misunderstanding of just how contingent history can be, how much can hinge on the efforts of a few people, or the unique circumstances of a time.

While there are technological and moral arcs to history, and they bend in predictable directions, the actual course events take depends at each moment upon the actions of that moment, upon the people there and what they choose to do.

A modern idiot dropped in 1986 can’t create Lougle just because he knows something called Google will exist anymore than he could kick-start the industrial revolution if he happened to be dropped in 1286. That’s just not how reality functions.

The Idea of a Thing is not its Name

I see this mistake happen a lot when writers try to incorporate technology into their stories. Often it’s clear the writer has no idea how the technology actually works or the conditions by which it was discovered, and so they-

-a writer, who understands the world through words first and foremost, who reduces all things to the shape and the form and the letters that make it up-

-simply assume that knowing the name of a thing is sufficient.

Like sorcerers of old, they seem to believe that knowing a things’ true name gives one mastery over it, such that knowing the name Google is sufficient to build the company from scratch if one had the chance.

(I understand that the whole thing is a joke. It’s funny. I laughed at it. But I see this mistake happen quite often, see word-people assume that technology can be reduced to the names we give it, and it irritates me that they don’t respect the sheer struggle and mastery over science and nature it requires to build something extraordinary.)

It’s as if the writers expect a scientist to be able to build a starship capable of faster-than-light travel, simply because they gave it a name: Warp Drive, like they think the hard part is done because the word has been created.

To be blunt: words are the easy part. Making up new words is not difficult. At this point, you can ask your friendly neighborhood LLM to make up new words, and it’ll give you as many as you like.

Hell, ‘LLM’, ‘Large Language Model’, is the name of a technology that very few people on earth could create from scratch, and yet were Hot Tub Time Machine to get a third entry today, I bet they’d crack a joke about the ‘Lou Language Model’.

In many magic systems (The Name of the Wind comes to mind), knowing a thing’s true name gives one power over it. But in reality, names are just shorthand ways of referring to things. That’s it. The idea of a thing - the true innovation or technology or innovation or knowledge - isn’t the name. And it’s ridiculous to think it could be.

So, are you saying the Dilithium Crystals I found in my back yard the other day are useless? Darn!