"I set out on this ground, which I suppose to be self-evident, ‘that the earth belongs in usufruct to the living’: that the dead have neither powers nor rights over it. The portion occupied by any individual ceases to be his when himself ceases to be, & reverts to the society. " -Thomas Jefferson

The Cemetery At The End Of The Lane

One of the pillars of Georgist thought is that land is vital and necessary for life - so why are we reserving so much of it for the dead?

In economics, we talk about opportunity costs: the idea that what isn’t done is just as important as what is. Money used to purchase food isn’t used to purchase flat-screen TVs. Time spent at the gym isn’t spent with family. When resources are finite, spending them one way necessarily means not spending them another way.

Land is the resource of main concern to Georgists, especially because land is a rivalrous good: land used for one purpose isn’t used for another.

I live in a populous area in Maryland, and every day on my way to work I pass by a vast cemetery. Rows upon rows of flowers mark the mortal remains slumbering beneath the ground; the occasional tombstone rises above the grass like a sentinel keeping watch, weather-worn but unbowed.

It’s not hard to imagine the solace a mourner might find as they lay a friend to rest or come to visit the graves of their parents. However, cemeteries aren’t parks - they aren’t multi-use public spaces, able to adapt to the needs of their communities. They’re exclusively used for the interment and remembrance of the dead.

So ask yourself - how often do you visit a cemetery? How much time do you spend there? Because land is a rivalrous good, and land which preserves the dead is unavailable to house the living. In a high cost-of-living area like mine, a place where people want to live but can’t afford to, cemeteries aren’t just places for mourners to mourn: they’re a tax the dead impose upon the living.

People Die Where They Live

This isn’t a new problem, or one that city planners are unaware of. A report authored by the American Planning Association from 1950 shows that even back then (when the US population was less than half of what it is today) the land used for burials was a concern:

In 1935, the U. S. Department of Commerce published an estimate of 15,000 cemeteries in the United States. There are no official estimates of the acreage contained in these cemeteries. If we assume the conservative figure of one acre per thousand population (see Table I) cemetery land in the United States would be approximately 140,000 acres. Quite probably the greater part lies within city limits.

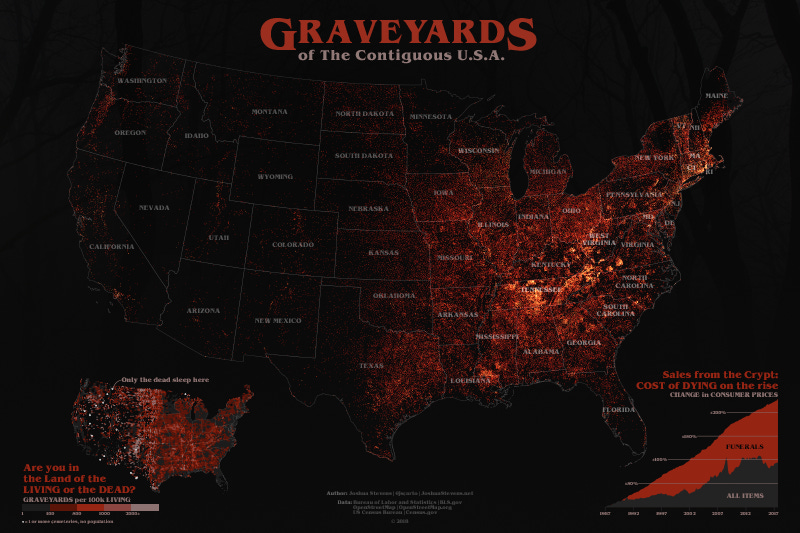

Compare this map (compiled by Joshua Stevens) of all the graveyards in the contiguous US today:

To a map of US population density from the 2020 census:

The overlap makes sense: people die where they live, so the most populous parts of the country should also have the most graveyards.

This generates a problem, however, as the number of graves increases monotonically over time. More and more space is taken up by the buried in areas that the living want to inhabit. Land prices are driven up by increased demand, and this economic surplus is captured by landowners.

The rents start high and get higher, while a massive amount of land that could be used to increase the supply of housing is left undeveloped, monopolized by the dead at the expense of the living.

Furthermore, cemeteries don’t support regular public gatherings like parks or other public spaces do. They aren’t used for hiking or backpacking; they don’t capture carbon through forestation or preserve valuable natural habitats.

They are an extremely unproductive use of land, right where land needs to be used productively the most.

Georgism’s Solution

So what would Georgism - a Land Value Tax (LVT), in other words - change?

Before anything else, a Georgist solution might involve actually taxing cemeteries.

Per Maryland law:

(a) Property owned by individuals or religious groups. -- Except as otherwise provided in subsection (b) of this section, property owned by an individual or a religious group is not subject to property tax if the property is actually used exclusively to bury dead individuals.

I haven’t seen many references to how Georgists feel about this (this Reddit thread is about it), but my personal sense is that no land should be exempt from the LVT. All land belongs to all people - what makes cemeteries and graveyards different?

Before we think about the practical changes a Georgist system would make, it’s important to affirm a commitment to the respectful treatment of the deceased.

Whenever land containing existing remains is redeveloped, legislation should mandate that (for example) all remains should be returned to the families to do with as they will, with a default of cremation if no family can be found.

It’s also important to be respectful of the religious and cultural practices surrounding treatment of the dead.

That being said, cemeteries in areas like mine are an inefficient use of land, and thus I would expect a large number of them to be unable to pay their LVT (if they can pay it then there isn’t a problem in the first place). They would be reclaimed by the government and auctioned off to a developer; I imagine the developer would hire a firm that specializes in the removal of existing remains to clear the grounds, after which development could begin, returning the land to the living.

A Georgist Future

So what does this Georgist future look like?

I’ll start with a few ideas for this possible future, and finish with a narrated glimpse at what could be.

Above all, though, it’s a place where life - and land - is for the living.

Ideas

Cremation

Cremation is the most popular choice for handling remains in this future, partly for the convenience and partly for the cost - cremation fees are considered a public health benefit and are therefore entirely covered by the state and funded by the LVT. This has the dual advantage of providing a respectful default for the remains of all people while also subsidizing the funereal costs of those who can’t afford a more elaborate solution.

Those who choose cremation have a number of options for what to do with the ashes of their loved ones. Many keep them safe in their homes and on their mantles, but others have chosen differently.

Ashes are mostly just carbon, and so the most common way to preserve a loved one’s ashes is to use them to create a synthetic diamond. Instead of decomposing below a patch of dirt, the dead can be turned into beautiful jewelry, preserving their atoms and their memory as family heirlooms.

Alternatively, many people specify in their wills for their ashes to be scattered in a favorite garden or park; some even choose exotic locations such as the ocean or atop a specific mountain.

Burial

Cemeteries and graveyards still exist in this future, but they’re either a) attached to other structures that justify the use of the land (such as being in the back of or beneath a church), b) far outside cities in land with little to no value, or c) property of the government, used for specific purposes.

Examples of c) include cemeteries of historical or national importance, such as Arlington National Cemetery or Gettysburg National Cemetery, which remain places where people can gather to remember United States history and honor our fallen heroes.

Another option for those who wish to bury their loved ones are the newly-created Samsara Orchards, where remains are interred in natural burials, without casket or embalming fluids, such that the body can fertilize the soil. Mourners spend time amongst the orchards, enjoying the shade provided by the boughs and the sweet aroma of apples and peaches. It’s a place to remember the dead, even as the fruits of the cycle of life are enjoyed.

Practically, the Samsara Orchards are located far outside cities, so the upkeep costs and minimal LVT are covered by modest burial fees and the sale of fruits, jams, and ciders. “Day of the Dead” style celebrations are had in autumn, where children are taught history and biology as they honor the dead and go apple-picking.

Mourning Gardens

Mourning is a central human experience, shared by everyone at one point or another in their lives. Much like other human needs (housing, connection, etc.), cities provide space for those who have lost someone and desire to be spiritually close to them.

The Mourning Gardens are these future-cities’ answer to this basic human need. Designed by artists and architects and filled with flora, these public spaces are curated by the city and provide meandering paths for mourners to wander. Multiple out-of-the-way nooks and secluded dead-ends provide privacy for those who want to be alone in their grief, but on the whole the gardens provide a place for communities to grieve together. Plants are often named after loved ones, and local residents are encouraged to add their own touches to the vibrant landscapes.

A Glimpse Of The (Georgist) Future

I breathe in, the air around me thick and sweet with a medley of floral aromas. A soft breeze ruffles my hair and disturbs the leafy canopy above me, sending dappled rays of sunlight and shadow dancing across the sky-blue hydrangeas blooming before me.

They always were my grandmother’s favorite.

Shaking my head, I blow out a long sigh and close my eyes, focusing on the warmth of the air and the rustling of leaves and branches that doesn’t quite mask the hum of the city in the background.

I always did get melancholic in the spring. Something about the world coming back to life after winter’s barren cold always made me think of the things that don’t come back, season after season.

The people that don’t come back.

My hand finds its way to my neck where, beneath my shirt, my necklace rests on my collarbones, the pendant attached to it dipping into the hollow of my throat. My grandmother’s atoms, the carbon cast into diamond by heat and pressure, sit there above my heart.

Crouching down, my other hand finds the petals of the hydrangea, satin-soft and fragile between my fingers. There’s a metaphor there for life - something about continuous renewal, or things being precious because they’re easily broken or lost, or how beauty is always temporary - but I banish the thought with a wry smile.

Too in your own head, my grandmother would have said.

I remembered the last time we meandered through the mourning garden together, our steps slow, almost stately, her arm linked with mine for balance. We’d known about the diagnosis for months now, and she wanted to come here with me at least once before the end.

We’d visited together before, of course, her and my mom and my sister and me. My grandmother went regularly; when I was young I asked my mother why, to which she replied that Grandma had her own mom and dad to mourn. My great-grandparents, who hung around my grandma’s neck in the form of a diamond necklace, who would one day hang around my own mother’s neck. It was the first time I realized that my mother had lost her own grandparents, and that one day I would lose mine.

Of course there was a large difference between knowing that my grandmother would be gone one day, and walking with her through the mourning garden, not knowing how many of these walks we’d have left.

Still, the garden was beautiful as always, a modest number of people around but in their own worlds, occupied by their own grief.

We came to a halt at my grandmother’s favorite nook, the hydrangeas in the full bloom of summer. Her wrinkled fingers reached out, plucking a petal from its stem and holding it in her hand.

Grief, she told me, is a part of life. And sometimes we need to be alone to grieve. She held up the petal. But grieving alone isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. Her palm opened and tipped over, causing the petal to flutter to the ground.

All these people, her hand gestured around us, have lost someone. But I like coming here, because it reminds me, no matter how sad I feel, that I’m not alone. Everyone grieves.

She turned towards me, her hand coming up to cup my cheek. I remember being shorter than her not that long ago, but she had to tilt her head up to meet my eyes.

I don’t want you to grieve alone, she said. After I’m gone.

I didn’t have a response then. My eyes were too watery, my throat too choked up. But as I let the memory fade in the afternoon light, I give the pendant around my neck a squeeze and stand up. The lone petal slips through the fingers of my other hand, retaking its place amongst its fellows in bloom.

I smile - small and sad, but a smile nonetheless - and leave the privacy of the little nook my grandmother and I favored. I pass by other mourners as I retrace my steps through the garden, offering them a quirk of my lips and a nod as I go. Just a small reminder that no one here is truly alone in their grief. Most don’t notice, but I see the few who do perk up a tad.

Stepping out of the mourning garden, I find myself back in the hustle and bustle of the city. Joining the flow of pedestrians, I make my way to the subway station, ground-level stores going by on either side with apartments rising atop them into the sky.

I had places to be, and as my grandmother would have said, life is for the living.